Fall Book List

The books we read should be chosen with great care,

that they may be, as an Egyptian king wrote over his library,

"The medicines of the soul."

~ Paxton Hood ~

Please read the following book by the last Friday of each month. We will have a discussion on the last Friday of each month. Please see the schedule page for more details.

December - Sarah's Key by Tatiana de Rosnay

January - The Passage by Justin Cronin

February - The Happiness Project by Gretchen Rubin

March - The Help by Kathryn Stockett

April - The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot

May - Matterhorn by Karl Marlantes

June - Measure of a Man by Sidney Poitier

December - Sarah's Key by Tatiana de Rosnay

January - The Passage by Justin Cronin

February - The Happiness Project by Gretchen Rubin

March - The Help by Kathryn Stockett

April - The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot

May - Matterhorn by Karl Marlantes

June - Measure of a Man by Sidney Poitier

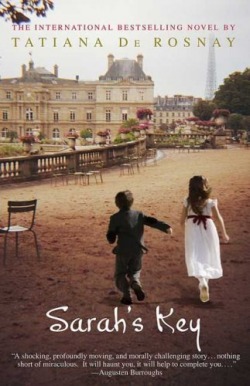

December - Sarah's Key

by Tatiana de Rosnay

Publishers Weekly Starred Review.

De Rosnay's U.S. debut fictionalizes the 1942 Paris roundups and deportations, in which thousands of Jewish families were arrested, held at the Vélodrome d'Hiver outside the city, then transported to Auschwitz. Forty-five-year-old Julia Jarmond, American by birth, moved to Paris when she was 20 and is married to the arrogant, unfaithful Bertrand Tézac, with whom she has an 11-year-old daughter. Julia writes for an American magazine and her editor assigns her to cover the 60th anniversary of the Vél' d'Hiv' roundups. Julia soon learns that the apartment she and Bertrand plan to move into was acquired by Bertrand's family when its Jewish occupants were dispossessed and deported 60 years before. She resolves to find out what happened to the former occupants: Wladyslaw and Rywka Starzynski, parents of 10-year-old Sarah and four-year-old Michel. The more Julia discovers—especially about Sarah, the only member of the Starzynski family to survive—the more she uncovers about Bertrand's family, about France and, finally, herself. Already translated into 15 languages, the novel is De Rosnay's 10th (but her first written in English, her first language). It beautifully conveys Julia's conflicting loyalties, and makes Sarah's trials so riveting, her innocence so absorbing, that the book is hard to put down. (July)

Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Review

“This is a remarkable historical novel, a book which brings to light a disturbing and deliberately hidden aspect of French behavior towards Jews during World War II. Like Sophie's Choice, it's a book that impresses itself upon one's heart and soul forever.”

–Naomi Ragen, author of The Saturday Wife and The Covenant

“Sarah's Key unlocks the star crossed, heart thumping story of an American journalist in Paris and the 60-year-old secret that could destroy her marriage. This book will stay on your mind long after it's back on the shelf.”

–Risa Miller, author of Welcome to Heavenly Heights

Publishers Weekly Starred Review.

De Rosnay's U.S. debut fictionalizes the 1942 Paris roundups and deportations, in which thousands of Jewish families were arrested, held at the Vélodrome d'Hiver outside the city, then transported to Auschwitz. Forty-five-year-old Julia Jarmond, American by birth, moved to Paris when she was 20 and is married to the arrogant, unfaithful Bertrand Tézac, with whom she has an 11-year-old daughter. Julia writes for an American magazine and her editor assigns her to cover the 60th anniversary of the Vél' d'Hiv' roundups. Julia soon learns that the apartment she and Bertrand plan to move into was acquired by Bertrand's family when its Jewish occupants were dispossessed and deported 60 years before. She resolves to find out what happened to the former occupants: Wladyslaw and Rywka Starzynski, parents of 10-year-old Sarah and four-year-old Michel. The more Julia discovers—especially about Sarah, the only member of the Starzynski family to survive—the more she uncovers about Bertrand's family, about France and, finally, herself. Already translated into 15 languages, the novel is De Rosnay's 10th (but her first written in English, her first language). It beautifully conveys Julia's conflicting loyalties, and makes Sarah's trials so riveting, her innocence so absorbing, that the book is hard to put down. (July)

Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Review

“This is a remarkable historical novel, a book which brings to light a disturbing and deliberately hidden aspect of French behavior towards Jews during World War II. Like Sophie's Choice, it's a book that impresses itself upon one's heart and soul forever.”

–Naomi Ragen, author of The Saturday Wife and The Covenant

“Sarah's Key unlocks the star crossed, heart thumping story of an American journalist in Paris and the 60-year-old secret that could destroy her marriage. This book will stay on your mind long after it's back on the shelf.”

–Risa Miller, author of Welcome to Heavenly Heights

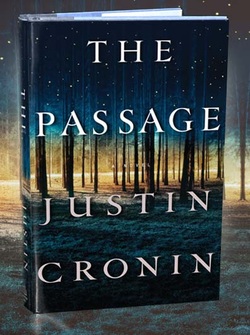

January - The Passage

by Justin Cronin

http://enterthepassage.com/

Amazon.com Review Amazon Best Books of the Month, June 2010: You don't have to be a fan of vampire fiction to be enthralled by The Passage, Justin Cronin's blazing new novel. Cronin is a remarkable storyteller (just ask adoring fans of his award-winning Mary and O'Neil), whose gorgeous writing brings depth and vitality to this ambitious epic about a virus that nearly destroys the world, and a six-year-old girl who holds the key to bringing it back. The Passage takes readers on a journey from the early days of the virus to the aftermath of the destruction, where packs of hungry infected scour the razed, charred cities looking for food, and the survivors eke out a bleak, brutal existence shadowed by fear. Cronin doesn't shy away from identifying his "virals" as vampires. But, these are not sexy, angsty vampires (you won’t be seeing "Team Babcock" t-shirts any time soon), and they are not old-school, evil Nosferatus, either. These are a creation all Cronin's own--hairless, insectile, glow-in-the-dark mutations who are inextricably linked to their makers and the one girl who could destroy them all. A huge departure from Cronin's first two novels, The Passage is a grand mashup of literary and supernatural, a stunning beginning to a trilogy that is sure to dazzle readers of both genres. --Daphne Durham

Dan Chaon Reviews The Passage

Dan Chaon is the acclaimed author of the national bestseller Await Your Reply and You Remind Me of Me, which was named one of the best books of the year by The Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, San Francisco Chronicle, The Christian Science Monitor, and Entertainment Weekly, among other publications. Chaon lives in Cleveland Heights, Ohio, and teaches at Oberlin College. Read his review of The Passage:

There is a particular kind of reading experience--the feeling you get when you can’t wait to find out what happens next, you can’t turn the pages fast enough, and yet at the same time you are so engaged in the world of the story and the characters, you don’t want it to end. It’s a rare and complex feeling--that plot urgency pulling you forward, that yearning for more holding you back. We say that we are swept up, that we are taken away. Perhaps this effect is one of the true magic tricks that literature can offer to us, and yet it doesn’t happen very often. Mostly, I think, we remember this experience from a few of the beloved books of our childhood.

About three-quarters of the way through The Passage, I found myself in the grip of that peculiar and intense readerly emotion. One part of my brain couldn’t wait to get to the next big revelation, and I found myself wanting to leapfrog from paragraph to paragraph, hurtling toward each looming climax. Meanwhile, another part of my brain was watching the dwindling final pages with dread, knowing that things would be over soon, and wishing to linger with each sentence and character a little while longer.

Finishing The Passage for the first time, I didn’t bother to put it on a shelf, because I knew I would be flipping back through its pages again the next day. Rereading. Considering.

Certain kinds of books draw us into the lives of their characters, into their inner thoughts, to the extent that we seem to know them, as well as we know real people. Readers of Justin Cronin’s earlier books, Mary and O’Neil and The Summer Guest, will recognize him as an extraordinarily insightful chronicler of the ways in which people maneuver through the past, and through loss, grief and love. Though The Passage is a different sort of book, Cronin hasn’t lost his skill for creating deeply moving character portraits. Throughout, in moments both large and small, readers will find the kind of complicated and heartfelt relationships that Cronin has made his specialty. Though the cast of characters is large, they are never mere pawns. The individual lives are brought to us with a vivid tenderness, and at the center of the story is not only vampires and gun battles but also quite simply a quiet meditation on the love of a man for his adopted daughter. As a fan of Cronin’s earlier work, I found it exciting to see him developing these thoughtful character studies in an entirely different context.

There are also certain kinds of books expand outwards beyond the borders of their covers. They make us wish for encyclopedias and maps, genealogies and indexes, appendixes that detail the adventures of the minor characters we loved but only briefly glimpsed. The Passage is that kind of book, too. There is a dense web of mythology and mystery that roots itself into your brain--even as you are turning the pages as quickly as you can. Complex secrets and untold stories peer out from the edges of the plot in a way that fires the imagination, so that the world of the novel seems to extend outwards, a whole universe--parts of which we glimpse in great detail--and yet we long to know even more. I hope it won’t be saying too much to say that there are actually two universes in this novel, one overlapping the other: there is the world before the virus, and the world after, and one of the pleasures of the book is the way that those two worlds play off one another, each one twisting off into a garden of forking and intertwined paths. I think, for example, of the scientist Jonas Lear, and his journey to a fabled site in the jungles of Bolivia where clouds of bats descend upon his team of researchers; or the little girl, Amy, whose trip to the zoo sets the animals into a frenzy--"They know what I am," she says; or one of the men in Dr. Lear’s experiment, Subject Zero, monitored in his cell as he hangs "like some kind of giant insect in the shadows." These characters and images weave their way through the story in different forms, recurring like icons, and there are threads to be connected, and threads we cannot quite connect--yet. And I hope that there will be some questions that will not be solved at all, that will just exist, as the universe of The Passage takes on a strange, uncanny life of its own.

It takes two different kinds of books to work a reader up into that hypnotic, swept away feeling. The author needs to create both a deep intimacy with the characters, and an expansive, strange-but-familiar universe that we can be immersed in. The Passage is one of those rare books that has both these elements. I envy those readers who are about to experience it for the first time.

Danielle Trussoni Reviews The Passage

Danielle Trussoni is the author of Falling Through the Earth: A Memoir, which was the recipient of the 2006 Michener-Copernicus Society of America Award, a BookSense pick, and one of The New York Times Ten Best Books of 2006. Her first novel Angelology will be published in 30 countries.

Read her review of The Passage:

Justin Cronin’s The Passage is a dark morality tale of just how frightening things can become when humanity transgresses the laws of nature.

The author of two previous novels, Cronin, in his third book, imagines the catastrophic possibilities of a vampiric bat virus unleashed upon the world. Discovered by the U.S. Military in South America, the virus is transported to a laboratory in the Colorado mountains where it is engineered to create a more invincible soldier. The virus’ potential benefits are profound: it has the power to make human beings immortal and indestructible. Yet, like Prometheus’ theft of fire from the Gods, knowledge and technological advancement are gained at great price: After the introduction of the virus into the human blood pool, it becomes clear that there will be hell to pay. The guinea pigs of the NOAH experiment, twelve men condemned to die on death row, become a superhuman race of vampire-like creatures called Virals. Soon, the population of the earth is either dead or infected, their minds controlled telepathically by the Virals. As most of human civilization has been wiped out by the Virals, the few surviving humans create settlements and live off the land with a fortitude the pilgrims would have admired. Only Amy, an abandoned little girl who becomes a mystical antidote to the creatures’ powers, will be able to save the world.

The Passage is no quick read, but a sweeping dystopian epic that will utterly transport one to another world, a place both haunting and horrifying to contemplate. Cronin weaves together multiple story lines that build into a journey spanning one hundred years and nearly 800 pages. While vampire lore lurks in the background--the Virals nick necks in order to infect humans, are immortal and virtually indestructible, and do most of their hunting at night--Cronin is more interested in creating an apocalyptic vision along the lines of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road.

Taking place in a futuristic America where New Orleans is a military zone, Jenna Bush is the Governor of Texas and citizens are under surveillance, The Passage offers a gruesome and twisted version of reality, a terrifying dream world in which our very worst nightmares come true. Ultimately, like the best fiction, The Passage explores what it means to be human in the face of overwhelming adversity. The thrill comes with the knowledge that Amy and the Virals must face off in a grand battle for the fate of humanity.

Questions for Justin Cronin

Q: What is The Passage?

A: A passage is, of course, a journey, and the novel is made up of journeys. But the notion of a journey in the novel, and indeed in the whole trilogy, is also metaphoric. A passage is a transition from one state or condition to another. The world itself makes such a transition in the book. So do all the characters—as characters in a novel must. The title is also a reference to the soul’s passage from life to death, and whatever lies in that unknown realm. Time and time again I’ve heard it, and in my own life, witnessed it: people at the end of life want to go home. It is a literal longing, I think, to leave this world while in a place of meaning, among familiar things and faces. But it is also a celestial longing.

Q: You are a PEN/Hemingway Award-winning author of literary fiction. Does The Passage represent a departure for you?

A: I think it’d be a little silly of me not to acknowledge that The Passage is, in a number of ways, overtly different from my other books. But rather than calling it a ‘departure,’ I’d prefer to describe it as a progression or evolution. First of all, the themes that engage me as a person and a writer are all still present. Love, sacrifice, friendship, loyalty, courage. The bonds between people, parents and children especially. The pull of history, and the power of place, of landscape, to shape experience. And I don’t think the writing itself is different at all. How could it be? You write how you write.

Q: The Passage takes place all across America--from Philadelphia to Houston to southern California. What prompted you to choose these specific locations?

A: Many of the major locations in the novel are, in fact, places I have lived. Except for a long stint in Philadelphia, and now Houston, my life has been a bit nomadic. I was raised in the Northeast, but after college, I ping-ponged all over the country for a while. In some ways, shaking off my strictly Northeastern point of view has been the central project of my adult life. This gave me not only a sense of the sheer immensity of the continent, but also the great diversity of its textures, both geographical and cultural, and I wanted the book to capture this feeling of vastness, especially when the narrative jumps forward a hundred years and the continent has become depopulated. One of the most striking impressions of my travels across the country is how empty a lot of it is. You can pull off the road in Kansas or Nevada or Utah or Texas and stand in the quiet with only the wind for company and it seems as if civilization has already ended, that you’re all alone on the planet. It’s a wonderful and a terrifying feeling at the same time, and while I was writing the book, I decided I would travel every mile my characters did, in order to capture not only the details of place, but the feeling of place.

The writer Charles Baxter once said (more or less) that you know you’ve come to the end of a story when you’ve found a way to get your characters back to where they started. The end of The Passage is meant to create another beginning, and the space for book two to unfold.

Q: Your daughter was the spark that set your writing of The Passage in motion. What else drove you to delve into such an epic undertaking?

A: The other force at work was something more personal and writerly. One of the reasons that the story of The Passage had such a magnetic effect on me was that I felt myself reclaiming the impulses that led me to become a writer in the first place. Like my daughter, I was a big reader as a kid. I lived in the country, with no other kids around, and spent most of my childhood either with my nose in a book or wandering around the woods with my head in some imagined narrative or another. It was much later, of course, that I formally became a student of literature, and decided that writing was something I wanted to do professionally. But the groundwork was all laid back then, reading with a flashlight under the covers.

Q: Did you have the narrative completely mapped out before you started, or did certain developments take you by surprise?

A: I had it mostly mapped out, but the book is in charge. I split and recombined some characters (mostly secondary ones.) I tend to think in terms of general narrative goals; the details work themselves out as you go, just so long as you remember the destination. And to that extent, the book followed the map I made with my daughter quite closely.

Q: When will we get to read the next book?

A: Two years (fingers wishfully crossed).

From Publishers Weekly

Starred Review. Fans of vampire fiction who are bored by the endless hordes of sensitive, misunderstood Byronesque bloodsuckers will revel in Cronin's engrossingly horrific account of a post-apocalyptic America overrun by the gruesome reality behind the wish-fulfillment fantasies. When a secret project to create a super-soldier backfires, a virus leads to a plague of vampiric revenants that wipes out most of the population. One of the few bands of survivors is the Colony, a FEMA-established island of safety bunkered behind massive banks of lights that repel the virals, or dracs—but a small group realizes that the aging technological defenses will soon fail. When members of the Colony find a young girl, Amy, living outside their enclave, they realize that Amy shares the virals' agelessness, but not the virals' mindless hunger, and they embark on a search to find answers to her condition. PEN/Hemingway Award–winner Cronin (The Summer Guest) uses a number of tropes that may be overly familiar to genre fans, but he manages to engage the reader with a sweeping epic style. The first of a proposed trilogy, it's already under development by director Ripley Scott and the subject of much publicity buzz (Retail Nation, Mar. 15). (June)

Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

http://enterthepassage.com/

Amazon.com Review Amazon Best Books of the Month, June 2010: You don't have to be a fan of vampire fiction to be enthralled by The Passage, Justin Cronin's blazing new novel. Cronin is a remarkable storyteller (just ask adoring fans of his award-winning Mary and O'Neil), whose gorgeous writing brings depth and vitality to this ambitious epic about a virus that nearly destroys the world, and a six-year-old girl who holds the key to bringing it back. The Passage takes readers on a journey from the early days of the virus to the aftermath of the destruction, where packs of hungry infected scour the razed, charred cities looking for food, and the survivors eke out a bleak, brutal existence shadowed by fear. Cronin doesn't shy away from identifying his "virals" as vampires. But, these are not sexy, angsty vampires (you won’t be seeing "Team Babcock" t-shirts any time soon), and they are not old-school, evil Nosferatus, either. These are a creation all Cronin's own--hairless, insectile, glow-in-the-dark mutations who are inextricably linked to their makers and the one girl who could destroy them all. A huge departure from Cronin's first two novels, The Passage is a grand mashup of literary and supernatural, a stunning beginning to a trilogy that is sure to dazzle readers of both genres. --Daphne Durham

Dan Chaon Reviews The Passage

Dan Chaon is the acclaimed author of the national bestseller Await Your Reply and You Remind Me of Me, which was named one of the best books of the year by The Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, San Francisco Chronicle, The Christian Science Monitor, and Entertainment Weekly, among other publications. Chaon lives in Cleveland Heights, Ohio, and teaches at Oberlin College. Read his review of The Passage:

There is a particular kind of reading experience--the feeling you get when you can’t wait to find out what happens next, you can’t turn the pages fast enough, and yet at the same time you are so engaged in the world of the story and the characters, you don’t want it to end. It’s a rare and complex feeling--that plot urgency pulling you forward, that yearning for more holding you back. We say that we are swept up, that we are taken away. Perhaps this effect is one of the true magic tricks that literature can offer to us, and yet it doesn’t happen very often. Mostly, I think, we remember this experience from a few of the beloved books of our childhood.

About three-quarters of the way through The Passage, I found myself in the grip of that peculiar and intense readerly emotion. One part of my brain couldn’t wait to get to the next big revelation, and I found myself wanting to leapfrog from paragraph to paragraph, hurtling toward each looming climax. Meanwhile, another part of my brain was watching the dwindling final pages with dread, knowing that things would be over soon, and wishing to linger with each sentence and character a little while longer.

Finishing The Passage for the first time, I didn’t bother to put it on a shelf, because I knew I would be flipping back through its pages again the next day. Rereading. Considering.

Certain kinds of books draw us into the lives of their characters, into their inner thoughts, to the extent that we seem to know them, as well as we know real people. Readers of Justin Cronin’s earlier books, Mary and O’Neil and The Summer Guest, will recognize him as an extraordinarily insightful chronicler of the ways in which people maneuver through the past, and through loss, grief and love. Though The Passage is a different sort of book, Cronin hasn’t lost his skill for creating deeply moving character portraits. Throughout, in moments both large and small, readers will find the kind of complicated and heartfelt relationships that Cronin has made his specialty. Though the cast of characters is large, they are never mere pawns. The individual lives are brought to us with a vivid tenderness, and at the center of the story is not only vampires and gun battles but also quite simply a quiet meditation on the love of a man for his adopted daughter. As a fan of Cronin’s earlier work, I found it exciting to see him developing these thoughtful character studies in an entirely different context.

There are also certain kinds of books expand outwards beyond the borders of their covers. They make us wish for encyclopedias and maps, genealogies and indexes, appendixes that detail the adventures of the minor characters we loved but only briefly glimpsed. The Passage is that kind of book, too. There is a dense web of mythology and mystery that roots itself into your brain--even as you are turning the pages as quickly as you can. Complex secrets and untold stories peer out from the edges of the plot in a way that fires the imagination, so that the world of the novel seems to extend outwards, a whole universe--parts of which we glimpse in great detail--and yet we long to know even more. I hope it won’t be saying too much to say that there are actually two universes in this novel, one overlapping the other: there is the world before the virus, and the world after, and one of the pleasures of the book is the way that those two worlds play off one another, each one twisting off into a garden of forking and intertwined paths. I think, for example, of the scientist Jonas Lear, and his journey to a fabled site in the jungles of Bolivia where clouds of bats descend upon his team of researchers; or the little girl, Amy, whose trip to the zoo sets the animals into a frenzy--"They know what I am," she says; or one of the men in Dr. Lear’s experiment, Subject Zero, monitored in his cell as he hangs "like some kind of giant insect in the shadows." These characters and images weave their way through the story in different forms, recurring like icons, and there are threads to be connected, and threads we cannot quite connect--yet. And I hope that there will be some questions that will not be solved at all, that will just exist, as the universe of The Passage takes on a strange, uncanny life of its own.

It takes two different kinds of books to work a reader up into that hypnotic, swept away feeling. The author needs to create both a deep intimacy with the characters, and an expansive, strange-but-familiar universe that we can be immersed in. The Passage is one of those rare books that has both these elements. I envy those readers who are about to experience it for the first time.

Danielle Trussoni Reviews The Passage

Danielle Trussoni is the author of Falling Through the Earth: A Memoir, which was the recipient of the 2006 Michener-Copernicus Society of America Award, a BookSense pick, and one of The New York Times Ten Best Books of 2006. Her first novel Angelology will be published in 30 countries.

Read her review of The Passage:

Justin Cronin’s The Passage is a dark morality tale of just how frightening things can become when humanity transgresses the laws of nature.

The author of two previous novels, Cronin, in his third book, imagines the catastrophic possibilities of a vampiric bat virus unleashed upon the world. Discovered by the U.S. Military in South America, the virus is transported to a laboratory in the Colorado mountains where it is engineered to create a more invincible soldier. The virus’ potential benefits are profound: it has the power to make human beings immortal and indestructible. Yet, like Prometheus’ theft of fire from the Gods, knowledge and technological advancement are gained at great price: After the introduction of the virus into the human blood pool, it becomes clear that there will be hell to pay. The guinea pigs of the NOAH experiment, twelve men condemned to die on death row, become a superhuman race of vampire-like creatures called Virals. Soon, the population of the earth is either dead or infected, their minds controlled telepathically by the Virals. As most of human civilization has been wiped out by the Virals, the few surviving humans create settlements and live off the land with a fortitude the pilgrims would have admired. Only Amy, an abandoned little girl who becomes a mystical antidote to the creatures’ powers, will be able to save the world.

The Passage is no quick read, but a sweeping dystopian epic that will utterly transport one to another world, a place both haunting and horrifying to contemplate. Cronin weaves together multiple story lines that build into a journey spanning one hundred years and nearly 800 pages. While vampire lore lurks in the background--the Virals nick necks in order to infect humans, are immortal and virtually indestructible, and do most of their hunting at night--Cronin is more interested in creating an apocalyptic vision along the lines of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road.

Taking place in a futuristic America where New Orleans is a military zone, Jenna Bush is the Governor of Texas and citizens are under surveillance, The Passage offers a gruesome and twisted version of reality, a terrifying dream world in which our very worst nightmares come true. Ultimately, like the best fiction, The Passage explores what it means to be human in the face of overwhelming adversity. The thrill comes with the knowledge that Amy and the Virals must face off in a grand battle for the fate of humanity.

Questions for Justin Cronin

Q: What is The Passage?

A: A passage is, of course, a journey, and the novel is made up of journeys. But the notion of a journey in the novel, and indeed in the whole trilogy, is also metaphoric. A passage is a transition from one state or condition to another. The world itself makes such a transition in the book. So do all the characters—as characters in a novel must. The title is also a reference to the soul’s passage from life to death, and whatever lies in that unknown realm. Time and time again I’ve heard it, and in my own life, witnessed it: people at the end of life want to go home. It is a literal longing, I think, to leave this world while in a place of meaning, among familiar things and faces. But it is also a celestial longing.

Q: You are a PEN/Hemingway Award-winning author of literary fiction. Does The Passage represent a departure for you?

A: I think it’d be a little silly of me not to acknowledge that The Passage is, in a number of ways, overtly different from my other books. But rather than calling it a ‘departure,’ I’d prefer to describe it as a progression or evolution. First of all, the themes that engage me as a person and a writer are all still present. Love, sacrifice, friendship, loyalty, courage. The bonds between people, parents and children especially. The pull of history, and the power of place, of landscape, to shape experience. And I don’t think the writing itself is different at all. How could it be? You write how you write.

Q: The Passage takes place all across America--from Philadelphia to Houston to southern California. What prompted you to choose these specific locations?

A: Many of the major locations in the novel are, in fact, places I have lived. Except for a long stint in Philadelphia, and now Houston, my life has been a bit nomadic. I was raised in the Northeast, but after college, I ping-ponged all over the country for a while. In some ways, shaking off my strictly Northeastern point of view has been the central project of my adult life. This gave me not only a sense of the sheer immensity of the continent, but also the great diversity of its textures, both geographical and cultural, and I wanted the book to capture this feeling of vastness, especially when the narrative jumps forward a hundred years and the continent has become depopulated. One of the most striking impressions of my travels across the country is how empty a lot of it is. You can pull off the road in Kansas or Nevada or Utah or Texas and stand in the quiet with only the wind for company and it seems as if civilization has already ended, that you’re all alone on the planet. It’s a wonderful and a terrifying feeling at the same time, and while I was writing the book, I decided I would travel every mile my characters did, in order to capture not only the details of place, but the feeling of place.

The writer Charles Baxter once said (more or less) that you know you’ve come to the end of a story when you’ve found a way to get your characters back to where they started. The end of The Passage is meant to create another beginning, and the space for book two to unfold.

Q: Your daughter was the spark that set your writing of The Passage in motion. What else drove you to delve into such an epic undertaking?

A: The other force at work was something more personal and writerly. One of the reasons that the story of The Passage had such a magnetic effect on me was that I felt myself reclaiming the impulses that led me to become a writer in the first place. Like my daughter, I was a big reader as a kid. I lived in the country, with no other kids around, and spent most of my childhood either with my nose in a book or wandering around the woods with my head in some imagined narrative or another. It was much later, of course, that I formally became a student of literature, and decided that writing was something I wanted to do professionally. But the groundwork was all laid back then, reading with a flashlight under the covers.

Q: Did you have the narrative completely mapped out before you started, or did certain developments take you by surprise?

A: I had it mostly mapped out, but the book is in charge. I split and recombined some characters (mostly secondary ones.) I tend to think in terms of general narrative goals; the details work themselves out as you go, just so long as you remember the destination. And to that extent, the book followed the map I made with my daughter quite closely.

Q: When will we get to read the next book?

A: Two years (fingers wishfully crossed).

From Publishers Weekly

Starred Review. Fans of vampire fiction who are bored by the endless hordes of sensitive, misunderstood Byronesque bloodsuckers will revel in Cronin's engrossingly horrific account of a post-apocalyptic America overrun by the gruesome reality behind the wish-fulfillment fantasies. When a secret project to create a super-soldier backfires, a virus leads to a plague of vampiric revenants that wipes out most of the population. One of the few bands of survivors is the Colony, a FEMA-established island of safety bunkered behind massive banks of lights that repel the virals, or dracs—but a small group realizes that the aging technological defenses will soon fail. When members of the Colony find a young girl, Amy, living outside their enclave, they realize that Amy shares the virals' agelessness, but not the virals' mindless hunger, and they embark on a search to find answers to her condition. PEN/Hemingway Award–winner Cronin (The Summer Guest) uses a number of tropes that may be overly familiar to genre fans, but he manages to engage the reader with a sweeping epic style. The first of a proposed trilogy, it's already under development by director Ripley Scott and the subject of much publicity buzz (Retail Nation, Mar. 15). (June)

Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

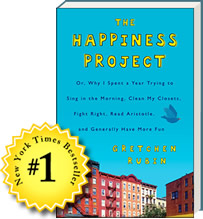

February - The Happiness Project

By: Gretchen Rubin

http://www.happiness-project.com/

From Publishers Weekly Starred Review. Rubin is not an unhappy woman: she has a loving husband, two great kids and a writing career in New York City. Still, she could-and, arguably, should-be happier. Thus, her methodical (and bizarre) happiness project: spend one year achieving careful, measurable goals in different areas of life (marriage, work, parenting, self-fulfillment) and build on them cumulatively, using concrete steps (such as, in January, going to bed earlier, exercising better, getting organized, and "acting more energetic"). By December, she's striving bemusedly to keep increasing happiness in every aspect of her life. The outcome is good, not perfect (in accordance with one of her "Secrets of Adulthood": "Don't let the perfect be the enemy of the good"), but Rubin's funny, perceptive account is both inspirational and forgiving, and sprinkled with just enough wise tips, concrete advice and timely research (including all those other recent books on happiness) to qualify as self-help. Defying self-help expectations, however, Rubin writes with keen senses of self and narrative, balancing the personal and the universal with a light touch. Rubin's project makes curiously compulsive reading, which is enough to make any reader happy.

Review “Packed with fascinating facts about the science of happiness and rich examples of how she improves her life through changes small and big The Happiness Project made me happier by just reading it.” (Amy Scribner, Bookpage )

“For those who generally loathe the self-help genre, Rubin’s book is a breath of peppermint-scented air. Well-researched and sharply written. . . . Rubin takes an orderly, methodical approach to forging her own path to a happier state of mind.” (Kim Crow, Cleveland Plain Dealer )

“Practical and never preachy . . . the rare self-help tome that doesn’t feel shameful to read.” (Daily Beast )

“An enlightening, laugh-aloud read. . . . Filled with open, honest glimpses into [Rubin’s] real life, woven together with constant doses of humor.” (Terry Hong, Christian Science Monitor )

http://www.happiness-project.com/

From Publishers Weekly Starred Review. Rubin is not an unhappy woman: she has a loving husband, two great kids and a writing career in New York City. Still, she could-and, arguably, should-be happier. Thus, her methodical (and bizarre) happiness project: spend one year achieving careful, measurable goals in different areas of life (marriage, work, parenting, self-fulfillment) and build on them cumulatively, using concrete steps (such as, in January, going to bed earlier, exercising better, getting organized, and "acting more energetic"). By December, she's striving bemusedly to keep increasing happiness in every aspect of her life. The outcome is good, not perfect (in accordance with one of her "Secrets of Adulthood": "Don't let the perfect be the enemy of the good"), but Rubin's funny, perceptive account is both inspirational and forgiving, and sprinkled with just enough wise tips, concrete advice and timely research (including all those other recent books on happiness) to qualify as self-help. Defying self-help expectations, however, Rubin writes with keen senses of self and narrative, balancing the personal and the universal with a light touch. Rubin's project makes curiously compulsive reading, which is enough to make any reader happy.

Review “Packed with fascinating facts about the science of happiness and rich examples of how she improves her life through changes small and big The Happiness Project made me happier by just reading it.” (Amy Scribner, Bookpage )

“For those who generally loathe the self-help genre, Rubin’s book is a breath of peppermint-scented air. Well-researched and sharply written. . . . Rubin takes an orderly, methodical approach to forging her own path to a happier state of mind.” (Kim Crow, Cleveland Plain Dealer )

“Practical and never preachy . . . the rare self-help tome that doesn’t feel shameful to read.” (Daily Beast )

“An enlightening, laugh-aloud read. . . . Filled with open, honest glimpses into [Rubin’s] real life, woven together with constant doses of humor.” (Terry Hong, Christian Science Monitor )

March - The Help

By: Kathryn Stockett

http://www.kathrynstockett.com/

From Publishers Weekly Starred Review. What perfect timing for this optimistic, uplifting debut novel (and maiden publication of Amy Einhorn's new imprint) set during the nascent civil rights movement in Jackson, Miss., where black women were trusted to raise white children but not to polish the household silver. Eugenia Skeeter Phelan is just home from college in 1962, and, anxious to become a writer, is advised to hone her chops by writing about what disturbs you. The budding social activist begins to collect the stories of the black women on whom the country club sets relies and mistrusts enlisting the help of Aibileen, a maid who's raised 17 children, and Aibileen's best friend Minny, who's found herself unemployed more than a few times after mouthing off to her white employers. The book Skeeter puts together based on their stories is scathing and shocking, bringing pride and hope to the black community, while giving Skeeter the courage to break down her personal boundaries and pursue her dreams. Assured and layered, full of heart and history, this one has bestseller written all over it. (Feb.)

Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

From Bookmarks Magazine In writing about such a troubled time in American history, Southern-born Stockett takes a big risk, one that paid off enormously. Critics praised Stockett's skillful depiction of the ironies and hypocrisies that defined an era, without resorting to depressing or controversial clich√©s. Rather, Stockett focuses on the fascinating and complex relationships between vastly different members of a household. Additionally, reviewers loved (and loathed) Stockett's three-dimensional characters—and cheered and hissed their favorites to the end. Several critics questioned Stockett's decision to use a heavy dialect solely for the black characters. Overall, however, The Help is a compassionate, original story, as well as an excellent choice for book groups.

http://www.kathrynstockett.com/

From Publishers Weekly Starred Review. What perfect timing for this optimistic, uplifting debut novel (and maiden publication of Amy Einhorn's new imprint) set during the nascent civil rights movement in Jackson, Miss., where black women were trusted to raise white children but not to polish the household silver. Eugenia Skeeter Phelan is just home from college in 1962, and, anxious to become a writer, is advised to hone her chops by writing about what disturbs you. The budding social activist begins to collect the stories of the black women on whom the country club sets relies and mistrusts enlisting the help of Aibileen, a maid who's raised 17 children, and Aibileen's best friend Minny, who's found herself unemployed more than a few times after mouthing off to her white employers. The book Skeeter puts together based on their stories is scathing and shocking, bringing pride and hope to the black community, while giving Skeeter the courage to break down her personal boundaries and pursue her dreams. Assured and layered, full of heart and history, this one has bestseller written all over it. (Feb.)

Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

From Bookmarks Magazine In writing about such a troubled time in American history, Southern-born Stockett takes a big risk, one that paid off enormously. Critics praised Stockett's skillful depiction of the ironies and hypocrisies that defined an era, without resorting to depressing or controversial clich√©s. Rather, Stockett focuses on the fascinating and complex relationships between vastly different members of a household. Additionally, reviewers loved (and loathed) Stockett's three-dimensional characters—and cheered and hissed their favorites to the end. Several critics questioned Stockett's decision to use a heavy dialect solely for the black characters. Overall, however, The Help is a compassionate, original story, as well as an excellent choice for book groups.

April - The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks

By: Rebecca Skloot

http://rebeccaskloot.com/the-immortal-life/

Amazon.com Review Amazon Best Books of the Month, February 2010: From a single, abbreviated life grew a seemingly immortal line of cells that made some of the most crucial innovations in modern science possible. And from that same life, and those cells, Rebecca Skloot has fashioned in The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks a fascinating and moving story of medicine and family, of how life is sustained in laboratories and in memory. Henrietta Lacks was a mother of five in Baltimore, a poor African American migrant from the tobacco farms of Virginia, who died from a cruelly aggressive cancer at the age of 30 in 1951. A sample of her cancerous tissue, taken without her knowledge or consent, as was the custom then, turned out to provide one of the holy grails of mid-century biology: human cells that could survive--even thrive--in the lab. Known as HeLa cells, their stunning potency gave scientists a building block for countless breakthroughs, beginning with the cure for polio. Meanwhile, Henrietta's family continued to live in poverty and frequently poor health, and their discovery decades later of her unknowing contribution--and her cells' strange survival--left them full of pride, anger, and suspicion. For a decade, Skloot doggedly but compassionately gathered the threads of these stories, slowly gaining the trust of the family while helping them learn the truth about Henrietta, and with their aid she tells a rich and haunting story that asks the questions, Who owns our bodies? And who carries our memories? --Tom Nissley

Amazon Exclusive: Jad Abumrad Reviews The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks

Jad Abumrad is host and creator of the public radio hit Radiolab, now in its seventh season and reaching over a million people monthly. Radiolab combines cutting-edge production with a philosophical approach to big ideas in science and beyond, and an inventive method of storytelling. Abumrad has won numerous awards, including a National Headliner Award in Radio and an American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) Science Journalism Award.

Read his exclusive Amazon guest review of The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks:

Honestly, I can't imagine a better tale.

A detective story that's at once mythically large and painfully intimate.

Just the simple facts are hard to believe: that in 1951, a poor black woman named Henrietta Lacks dies of cervical cancer, but pieces of the tumor that killed her--taken without her knowledge or consent--live on, first in one lab, then in hundreds, then thousands, then in giant factories churning out polio vaccines, then aboard rocket ships launched into space. The cells from this one tumor would spawn a multi-billion dollar industry and become a foundation of modern science--leading to breakthroughs in gene mapping, cloning and fertility and helping to discover how viruses work and how cancer develops (among a million other things). All of which is to say: the science end of this story is enough to blow one's mind right out of one's face.

But what's truly remarkable about Rebecca Skloot's book is that we also get the rest of the story, the part that could have easily remained hidden had she not spent ten years unearthing it: Who was Henrietta Lacks? How did she live? How she did die? Did her family know that she'd become, in some sense, immortal, and how did that affect them? These are crucial questions, because science should never forget the people who gave it life. And so, what unfolds is not only a reporting tour de force but also a very entertaining account of Henrietta, her ancestors, her cells and the scientists who grew them.

The book ultimately channels its journey of discovery though Henrietta's youngest daughter, Deborah, who never knew her mother, and who dreamt of one day being a scientist.

As Deborah Lacks and Skloot search for answers, we're bounced effortlessly from the tiny tobacco-farming Virginia hamlet of Henrietta's childhood to modern-day Baltimore, where Henrietta's family remains. Along the way, a series of unforgettable juxtapositions: cell culturing bumps into faith healings, cutting edge medicine collides with the dark truth that Henrietta's family can't afford the health insurance to care for diseases their mother's cells have helped to cure.

Rebecca Skloot tells the story with great sensitivity, urgency and, in the end, damn fine writing. I highly recommend this book. --Jad Abumrad

http://rebeccaskloot.com/the-immortal-life/

Amazon.com Review Amazon Best Books of the Month, February 2010: From a single, abbreviated life grew a seemingly immortal line of cells that made some of the most crucial innovations in modern science possible. And from that same life, and those cells, Rebecca Skloot has fashioned in The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks a fascinating and moving story of medicine and family, of how life is sustained in laboratories and in memory. Henrietta Lacks was a mother of five in Baltimore, a poor African American migrant from the tobacco farms of Virginia, who died from a cruelly aggressive cancer at the age of 30 in 1951. A sample of her cancerous tissue, taken without her knowledge or consent, as was the custom then, turned out to provide one of the holy grails of mid-century biology: human cells that could survive--even thrive--in the lab. Known as HeLa cells, their stunning potency gave scientists a building block for countless breakthroughs, beginning with the cure for polio. Meanwhile, Henrietta's family continued to live in poverty and frequently poor health, and their discovery decades later of her unknowing contribution--and her cells' strange survival--left them full of pride, anger, and suspicion. For a decade, Skloot doggedly but compassionately gathered the threads of these stories, slowly gaining the trust of the family while helping them learn the truth about Henrietta, and with their aid she tells a rich and haunting story that asks the questions, Who owns our bodies? And who carries our memories? --Tom Nissley

Amazon Exclusive: Jad Abumrad Reviews The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks

Jad Abumrad is host and creator of the public radio hit Radiolab, now in its seventh season and reaching over a million people monthly. Radiolab combines cutting-edge production with a philosophical approach to big ideas in science and beyond, and an inventive method of storytelling. Abumrad has won numerous awards, including a National Headliner Award in Radio and an American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) Science Journalism Award.

Read his exclusive Amazon guest review of The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks:

Honestly, I can't imagine a better tale.

A detective story that's at once mythically large and painfully intimate.

Just the simple facts are hard to believe: that in 1951, a poor black woman named Henrietta Lacks dies of cervical cancer, but pieces of the tumor that killed her--taken without her knowledge or consent--live on, first in one lab, then in hundreds, then thousands, then in giant factories churning out polio vaccines, then aboard rocket ships launched into space. The cells from this one tumor would spawn a multi-billion dollar industry and become a foundation of modern science--leading to breakthroughs in gene mapping, cloning and fertility and helping to discover how viruses work and how cancer develops (among a million other things). All of which is to say: the science end of this story is enough to blow one's mind right out of one's face.

But what's truly remarkable about Rebecca Skloot's book is that we also get the rest of the story, the part that could have easily remained hidden had she not spent ten years unearthing it: Who was Henrietta Lacks? How did she live? How she did die? Did her family know that she'd become, in some sense, immortal, and how did that affect them? These are crucial questions, because science should never forget the people who gave it life. And so, what unfolds is not only a reporting tour de force but also a very entertaining account of Henrietta, her ancestors, her cells and the scientists who grew them.

The book ultimately channels its journey of discovery though Henrietta's youngest daughter, Deborah, who never knew her mother, and who dreamt of one day being a scientist.

As Deborah Lacks and Skloot search for answers, we're bounced effortlessly from the tiny tobacco-farming Virginia hamlet of Henrietta's childhood to modern-day Baltimore, where Henrietta's family remains. Along the way, a series of unforgettable juxtapositions: cell culturing bumps into faith healings, cutting edge medicine collides with the dark truth that Henrietta's family can't afford the health insurance to care for diseases their mother's cells have helped to cure.

Rebecca Skloot tells the story with great sensitivity, urgency and, in the end, damn fine writing. I highly recommend this book. --Jad Abumrad

May - Matterhorn

By: Karl Marlantes

Amazon.com Review Amazon Best Books of the Month, March 2010: Matterhorn is a marvel--a living, breathing book with Lieutenant Waino Mellas and the men of Bravo Company at its raw and battered heart. Karl Marlantes doesn't introduce you to Vietnam in his brilliant war epic--he unceremoniously drops you into the jungle, disoriented and dripping with leeches, with only the newbie lieutenant as your guide. Mellas is a bundle of anxiety and ambition, a college kid who never imagined being part of a "war that none of his friends thought was worth fighting," who realized too late that "because of his desire to look good coming home from a war, he might never come home at all." A highly decorated Vietnam veteran himself, Marlantes brings the horrors and heroism of war to life with the finesse of a seasoned writer, exposing not just the things they carry, but the fears they bury, the friends they lose, and the men they follow. Matterhorn is as much about the development of Mellas from boy to man, from the kind of man you fight beside to the man you fight for, as it is about the war itself. Through his untrained eyes, readers gain a new perspective on the ravages of war, the politics and bureaucracy of the military, and the peculiar beauty of brotherhood. --Daphne Durham

Amazon Exclusive: Mark Bowden Reviews Matterhorn: A Novel of the Vietnam War

Mark Bowden is the bestselling author of Black Hawk Down: A Story of Modern War, as well as The Best Game Ever, Bringing the Heat, Killing Pablo, and Guests of the Ayatollah. He reported at The Philadelphia Inquirer for twenty years and now writes for Vanity Fair, The Atlantic, and other magazines. He lives in Oxford, Pennsylvania.

Matterhorn is a great novel. There have been some very good novels about the Vietnam War, but this is the first great one, and I doubt it will ever be surpassed. Karl Marlantes overlooks no part of the experience, large or small, from a terrified soldier pondering the nature of good and evil, to the feel and smell of wet earth against scorched skin as a man tries to press himself into the ground to escape withering fire. Here is story-telling so authentic, so moving and so intense, so relentlessly dramatic, that there were times I wasn’t sure I could stand to turn the page. As with the best fiction, I was sad to reach the end.

The wrenching combat in Matterhorn is ultimately pointless; the marines know they are fighting a losing battle in the long run. Bravo Company carves out a fortress on the top of the hill so named, one of countless low, jungle-coated mountains near the border of Laos, only to be ordered to abandon it when they are done. After the enemy claims the hill’s deep bunkers and carefully constructed fields of fire, the company is ordered to take it back, to assault their own fortifications. They do so with devastating consequences, only to be ordered in the end to abandon Matterhorn once again.

Against this backdrop of murderous futility, Marlantes’ memorable collection of marines is pushed to its limits and beyond. As the deaths and casualties mount, the men display bravery and cowardice, ferocity and timidity, conviction and doubt, hatred and love, intelligence and stupidity. Often these opposites are contained in the same person, especially in the book’s compelling main character, Second Lt. Waino Mellas. As Mellas and his men struggle to overcome impossible barriers of landscape, they struggle to overcome similarly impossible barriers between each other, barriers of race and class and rank. Survival forces them to cling to each other and trust each other and ultimately love each other. There has never been a more realistic portrait or eloquent tribute to the nobility of men under fire, and never a more damning portrait of a war that ground them cruelly underfoot for no good reason.

Marlantes brilliantly captures the way combat morphs into clean abstraction as fateful decisions move up the chain of command, further and further away from the actual killing and dying. But he is too good a novelist to paint easy villains. His commanders make brave decisions and stupid ones. High and low there is the same mix of cowardice and bravery, ambition and selflessness, ineptitude and competence.

There are passages in this book that are as good as anything I have ever read. This one comes late in the story, when the main character, Mellas, has endured much, has killed and also confronted the immediate likelihood of his own death, and has digested the absurdity of his mission: "He asked for nothing now, nor did he wonder if he had been good or bad. Such concepts were all part of the joke he’d just discovered. He cursed God directly for the savage joke that had been played on him. And in that cursing Mellas for the first time really talked with his God. Then he cried, tears and snot mixing together as they streamed down his face, but his cries were the rage and hurt of a newborn child, at last, however roughly, being taken from the womb."

Vladimir Nabokov once said that the greatest books are those you read not just with your heart or your mind, but with your spine. This is one for the spine. --Mark Bowden

From Publishers Weekly

Starred Review. Thirty years in the making, Marlantes's epic debut is a dense, vivid narrative spanning many months in the lives of American troops in Vietnam as they trudge across enemy lines, encountering danger from opposing forces as well as on their home turf. Marine lieutenant and platoon commander Waino Mellas is braving a 13-month tour in Quang-Tri province, where he is assigned to a fire-support base and befriends Hawke, older at 22; both learn about life, loss, and the horrors of war. Jungle rot, leeches dropping from tree branches, malnourishment, drenching monsoons, mudslides, exposure to Agent Orange, and wild animals wreak havoc as brigade members face punishing combat and grapple with bitterness, rage, disease, alcoholism, and hubris. A decorated Vietnam veteran, the author clearly understands his playing field (including military jargon that can get lost in translation), and by examining both the internal and external struggles of the battalion, he brings a long, torturous war back to life with realistic characters and authentic, thrilling combat sequences. Marlantes's debut may be daunting in length, but it remains a grand, distinctive accomplishment. (Apr.)

Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Amazon.com Review Amazon Best Books of the Month, March 2010: Matterhorn is a marvel--a living, breathing book with Lieutenant Waino Mellas and the men of Bravo Company at its raw and battered heart. Karl Marlantes doesn't introduce you to Vietnam in his brilliant war epic--he unceremoniously drops you into the jungle, disoriented and dripping with leeches, with only the newbie lieutenant as your guide. Mellas is a bundle of anxiety and ambition, a college kid who never imagined being part of a "war that none of his friends thought was worth fighting," who realized too late that "because of his desire to look good coming home from a war, he might never come home at all." A highly decorated Vietnam veteran himself, Marlantes brings the horrors and heroism of war to life with the finesse of a seasoned writer, exposing not just the things they carry, but the fears they bury, the friends they lose, and the men they follow. Matterhorn is as much about the development of Mellas from boy to man, from the kind of man you fight beside to the man you fight for, as it is about the war itself. Through his untrained eyes, readers gain a new perspective on the ravages of war, the politics and bureaucracy of the military, and the peculiar beauty of brotherhood. --Daphne Durham

Amazon Exclusive: Mark Bowden Reviews Matterhorn: A Novel of the Vietnam War

Mark Bowden is the bestselling author of Black Hawk Down: A Story of Modern War, as well as The Best Game Ever, Bringing the Heat, Killing Pablo, and Guests of the Ayatollah. He reported at The Philadelphia Inquirer for twenty years and now writes for Vanity Fair, The Atlantic, and other magazines. He lives in Oxford, Pennsylvania.

Matterhorn is a great novel. There have been some very good novels about the Vietnam War, but this is the first great one, and I doubt it will ever be surpassed. Karl Marlantes overlooks no part of the experience, large or small, from a terrified soldier pondering the nature of good and evil, to the feel and smell of wet earth against scorched skin as a man tries to press himself into the ground to escape withering fire. Here is story-telling so authentic, so moving and so intense, so relentlessly dramatic, that there were times I wasn’t sure I could stand to turn the page. As with the best fiction, I was sad to reach the end.

The wrenching combat in Matterhorn is ultimately pointless; the marines know they are fighting a losing battle in the long run. Bravo Company carves out a fortress on the top of the hill so named, one of countless low, jungle-coated mountains near the border of Laos, only to be ordered to abandon it when they are done. After the enemy claims the hill’s deep bunkers and carefully constructed fields of fire, the company is ordered to take it back, to assault their own fortifications. They do so with devastating consequences, only to be ordered in the end to abandon Matterhorn once again.

Against this backdrop of murderous futility, Marlantes’ memorable collection of marines is pushed to its limits and beyond. As the deaths and casualties mount, the men display bravery and cowardice, ferocity and timidity, conviction and doubt, hatred and love, intelligence and stupidity. Often these opposites are contained in the same person, especially in the book’s compelling main character, Second Lt. Waino Mellas. As Mellas and his men struggle to overcome impossible barriers of landscape, they struggle to overcome similarly impossible barriers between each other, barriers of race and class and rank. Survival forces them to cling to each other and trust each other and ultimately love each other. There has never been a more realistic portrait or eloquent tribute to the nobility of men under fire, and never a more damning portrait of a war that ground them cruelly underfoot for no good reason.

Marlantes brilliantly captures the way combat morphs into clean abstraction as fateful decisions move up the chain of command, further and further away from the actual killing and dying. But he is too good a novelist to paint easy villains. His commanders make brave decisions and stupid ones. High and low there is the same mix of cowardice and bravery, ambition and selflessness, ineptitude and competence.

There are passages in this book that are as good as anything I have ever read. This one comes late in the story, when the main character, Mellas, has endured much, has killed and also confronted the immediate likelihood of his own death, and has digested the absurdity of his mission: "He asked for nothing now, nor did he wonder if he had been good or bad. Such concepts were all part of the joke he’d just discovered. He cursed God directly for the savage joke that had been played on him. And in that cursing Mellas for the first time really talked with his God. Then he cried, tears and snot mixing together as they streamed down his face, but his cries were the rage and hurt of a newborn child, at last, however roughly, being taken from the womb."

Vladimir Nabokov once said that the greatest books are those you read not just with your heart or your mind, but with your spine. This is one for the spine. --Mark Bowden

From Publishers Weekly

Starred Review. Thirty years in the making, Marlantes's epic debut is a dense, vivid narrative spanning many months in the lives of American troops in Vietnam as they trudge across enemy lines, encountering danger from opposing forces as well as on their home turf. Marine lieutenant and platoon commander Waino Mellas is braving a 13-month tour in Quang-Tri province, where he is assigned to a fire-support base and befriends Hawke, older at 22; both learn about life, loss, and the horrors of war. Jungle rot, leeches dropping from tree branches, malnourishment, drenching monsoons, mudslides, exposure to Agent Orange, and wild animals wreak havoc as brigade members face punishing combat and grapple with bitterness, rage, disease, alcoholism, and hubris. A decorated Vietnam veteran, the author clearly understands his playing field (including military jargon that can get lost in translation), and by examining both the internal and external struggles of the battalion, he brings a long, torturous war back to life with realistic characters and authentic, thrilling combat sequences. Marlantes's debut may be daunting in length, but it remains a grand, distinctive accomplishment. (Apr.)

Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

June - Measure of a Man

By: Sidney Poitier

From Publishers Weekly Given the personal nature of this narrative, it's impossible to imagine hearing anyone other than Poitier, with his distinctive, resonant voice and perfect enunciation, tell the story. In his second memoir Poitier talks about his childhood in the Caribbean, where he was terribly poor by American standards, but quite happy, swimming and climbing all he could. One of eight kids, Poitier was sent to live with an older brother in Miami when he started to get into difficulties as a teen. But frustrated by his inability to earn a living and by the disparaging way whites treated him, Poitier left Miami for New York. There he worked as a dishwasher, started a drama class and launched a celebrated acting career that led to starring roles in such classics as To Sir, with Love and Raisin in the Sun. Poitier's rendition of these events is so moving that listeners will wish this audio adaptation were twice as long. Simultaneous release with the Harper San Francisco hardcover (Forecasts, May 1).

Copyright 2000 Reed Business Information, Inc. --This text refers to the Audio Cassette edition.

From Library Journal Following his autobiography (This Life); something with a spiritual dimension.

Copyright 2000 Reed Business Information, Inc. --This text refers to an out of print or unavailable edition of this title.

From Publishers Weekly Given the personal nature of this narrative, it's impossible to imagine hearing anyone other than Poitier, with his distinctive, resonant voice and perfect enunciation, tell the story. In his second memoir Poitier talks about his childhood in the Caribbean, where he was terribly poor by American standards, but quite happy, swimming and climbing all he could. One of eight kids, Poitier was sent to live with an older brother in Miami when he started to get into difficulties as a teen. But frustrated by his inability to earn a living and by the disparaging way whites treated him, Poitier left Miami for New York. There he worked as a dishwasher, started a drama class and launched a celebrated acting career that led to starring roles in such classics as To Sir, with Love and Raisin in the Sun. Poitier's rendition of these events is so moving that listeners will wish this audio adaptation were twice as long. Simultaneous release with the Harper San Francisco hardcover (Forecasts, May 1).

Copyright 2000 Reed Business Information, Inc. --This text refers to the Audio Cassette edition.

From Library Journal Following his autobiography (This Life); something with a spiritual dimension.

Copyright 2000 Reed Business Information, Inc. --This text refers to an out of print or unavailable edition of this title.